There’s no denying that vintage luxury super clone watches are an endless source of fascination to watch collectors. Most of them predate the quartz watch era and make use of a mechanical movement (either hand-winding or self-winding) that requires some sort of interaction with the wearer. A spring stores energy and then disseminates that energy to the rest of the watch movement, which includes a series off levers, gears, jewels and other tiny parts. There’s a strange type of poetry to the whole thing that’s difficult to explain — “a little city” on the wrist is how many a watch movement has been described upon viewing.

Of course, many of these 1:1 UK replica watches are also decades old and have some sort of damage, even if that damage is superficial. A discolored dial, a faded bezel. This is damage. There is no other word for it.

…or is there?

The Rise of Patina

20+ years ago, the vintage watch market, such as it was, didn’t value watches with patina, or, in other words, Swiss super clone watches that showed their age, to nearly the same degree as it does today. James Lamdin, founder and CEO of NYC-based Analog/Shift, notes that “In the early days I was guided to ‘buy what I loved’ and not to overthink any of the financial/investment/originality angles.”

It’s a beautiful thought, and one I always hold close, but as the market has evolved and real values are now accompanying quality vintage timepieces, it is important to collect with a broader understanding of the whys/hows/and whats, and not just buy something because you like it.

In other words, before vintage AAA Swiss made fake watches started carrying more substantial values, the whole point was to buy what you liked and put no thought into the rest of it. With this basic mindset in place, it is definitely understandable that there was less emphasis on ‘originality’ — a confusing term with vintage wristwatches in particular — and more emphasis on aesthetics and history.”

So what changed? As Eric Wind, watch expert and owner of vintage watch dealer Wind Vintage, continues, “There was a broad evolution in collecting, across many different categories, to prefer original, untouched, and unrestored pieces compared to those made to look ‘new.’ That is the case for coin collecting, where coins that had cleaning in the past are hardly sellable. Likewise, cars that are too heavily restored are also becoming harder to sell as people now are beginning to prefer unrestored cars with their original paint and seats. Likewise, paintings that have had significant restoration are also more difficult to sell today than in the past.”

Now, we’re all crying our eyes out about originality. About correctness. About honesty. Prior to several years ago, I had never heard the word “correct” employed with respect to cheap super clone watches. “What does that even mean,” I thought, the first time I heard the term. That somebody mistook a piece of the watch for something it’s not? Well, sort of. A watch part being “correct” means that it’s the right part for that particular watch reference — in other words, the watch would have been “born” (read: left the factory) with that crown, dial, bracelet or what-have-you, or, if the part is a replacement, it’s of the type that would have been born with that watch.

This idea of correctness and originality is more important now than ever. People don’t want replaced parts, even if that part improves the functionality of the watch. Several large Swiss companies, for example, are famous (notorious?) for updating parts to modern spec on best copy watches that they receive back for service. Though I have yet to experience this myself, there are myriad stories floating around in the watch world about an unsuspecting individual taking his or her vintage watch in to have it serviced, only to have it returned to him or her with, say, a modern Super-LumiNova dial in place of the original tritium one, thereby destroying much of the value of the watch.

Why would a company do this? Well, Super-LumiNova, by way of example, is a “superior” material to tritium in that it’s not, you know, radioactive and stuff, and though it needs to be “charged” with light in order to glow, its glow “output” will remain constant for longer. In Brand X’s eyes, by bringing a watch up to modern spec with a new Super-LumiNova dial, it’s keeping the watch current, and this is the only way to deliver a watch back to a customer that is upheld by the brand’s warranty. Can’t argue with that. The problem is that watch people aren’t logical. If we really gave two shits about modern, superior technology, would we really be pouring money into analog super clone watches for sale?

Tritium fades over time and changes color, giving it a cool patina. It fades. It shows age. Super-LumiNova does not. And since so many of us value these qualities, the market has responded accordingly. By flipping out that faded tritium dial for a modern Super-LumiNova version, one is destroying the resell value of the watch, which naturally pisses the owner off. When your $20,000 watch is now worth less than half that, one is naturally upset.

But of course, an appreciation and willingness to pay for patina are about more than just aesthetics. People also love a good story, and that story extends to the stories of objects. When you look at a faded dial, or an oddly shaped chip in a watch case, or a worn bezel, you inevitably start thinking to yourself, “I wonder where that thing has been. What it’s seen.” I bought a vintage watch because the dial reminded me of the Negev Desert in Israel, a country in which I lived for a few years. I am all but devoid of any semblance of a logical explanation for this. I tried to justify the purpose to myself in other ways. “It’s top replica Rolex watches, thus it will retain its value well.” “It’s a 34mm Oyster — these are relatively undervalued.” “This watch will always remind me of my friends from whom I bought the watch (this one is true).” “This watch is a great size.”

Nope. I mean, those things might be true, each in varying degrees, but at the end of the day, the textured dial on that particular wholesale super clone Rolex ref. 6294 watches had turned a beige, sandy color from exposure to sun and possibly moisture, with darker spots in the center where the radium from the hands had “burned” it. It immediately reminded me of the Negev, a place for which I feel a deep affinity.

It also reminded me of its own era (the mid-1950s), of another time, a time during which I most certainly had never been alive or had directly experienced. Makes no sense — but I bought the watch. So much for logic. A vintage watch, like any other old object, is a stand-in for a type of liminal space — a gateway.

Eric Wind agrees: “Overall, it is the aesthetic of untouched, original watches — Swiss movements fake watches that look like they tell a story, or the kind of watch you wish you could inherit from your father or grandfathers — that I really love.”

Can’t argue with that, either.

Where Does Watch Patina Come From?

Recently, there has been much made of so-called “tropical” dials, which are dials on vintage super clone watches online that have turned uniformly brown. These dials weren’t “born” this way — they were for the most part originally black, and oxidation of the paint mixture used to manufacture the dials caused them to turn brown. Vintage watch collectors love this. And what about other types of patina?

So-called “Radium burn” falls into a similar category. For the first half of the 20th century, watch manufacturers used radium, a wildly radioactive material, to coat watch hands and dials, as it, you know, glowed in the dark. Sometimes the radium from the hands of a radium-painted watch would “burn” the dial, discoloring the paint beneath it and resulting in interesting patterns vaguely shaped like the watch’s hands. Radium burn is often asymmetrical and ugly, staining a perfectly good (or otherwise perfectly patina’d) dial. This is a defect, or more accurately, it is damage resulting from the radium-based paint, but, predictably, many in the watch world are bonkers for this look. Sometimes, it’s even beautiful.

Zoom out, and it’s all a bit ridiculous. Actually, it’s highly ridiculous: very often you’ll find a mid-30s dude standing in a vintage watch retailer being shown a radium-burned dial, his eyes bugging out behind his glasses in genuine fascination, and his poor fiancé standing behind him, nodding politely, wondering when this absurd transaction is going to finally be over, and when she can go home and resume her evening of things not burned by radioactive substances or bleached by the sun into a different color entirely.

One sympathizes.

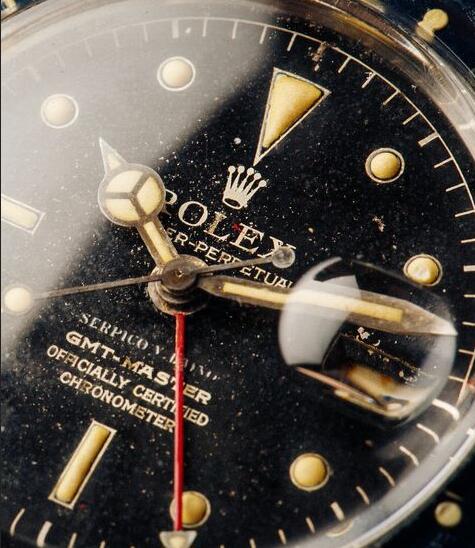

And bezels — what happens to those? Well, Bakelite, one of the first synthetic plastics, was once used to make bezels, including that of the very first high quality Rolex GMT Master replica watches, the 6542. Because these and similar bezels were prone to cracking and breakage, they are now rare, and highly sought after. (Some were even made of Bakelite and contained radium, making them breakable and dangerous. Twice the fun!) Many of them also faded in the sun — even the aluminum replacements that came later faded in the sun.

The interesting thing is that no two faded alike, so even if you compare two bezels produced for the perfect super clone Rolex GMT Master ref. 1675 watches, which shipped, in its most famous iteration, with a half-red, half-blue bezel, they won’t match. Sometimes you’ll get one on which the red half has faded to a beautiful magenta color, and the deep blue to a sky blue. If you peruse 10 different examples, the crazier (read, technically: “worse”) the fade, very often the higher the price. Wear! Hard use! Story! COOL!

Patina may technically be damage, but it’s the damage that makes these objects beautiful in the eye of the beholder. You’ll hear collectors speaking often about the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, or the acceptance of imperfection. This type of aesthetic has its own allure, and much of it is centered on this philosophy that beauty is impermanent and imperfect. It’s a convenient philosophy to espouse, even if you don’t believe it, as perfect, minty or New Old Stock watches are simply fewer and farther between than ever before. There are many, many more best quality fake watches with heavy patina floating around out there than there are watches new-in-box.

So What Exactly is an “Honest” Watch?

There’s another hot term that’s been making the rounds lately in vintage watch circles (and particularly in the auction world), and that’s the word “honest.” What does this mean with respect to super clone watches for men and women? That your watch was home by 9 pm and practiced safe timekeeping? That your watch would never dare adorn the wrist of another partner?

Close. It means, roughly, depending upon your interpretation, that a watch has retained its “correct” parts and not been messed with, or, more commonly, that a watch hasn’t been a “safe queen,” meaning that it’s lived a real life on somebody’s wrist — it might be nicked up, it might be faded, its bracelet might be stretched, but it’s seen some shit. Many of the heavily patina’d replica watches shop site you see at Christie’s, Phillips and Antiquorum now carry this description.

Is this a legitimate term to use? Who’s to say. You could be cynical and take the angle that this is merely a bullshit euphemism invented by wealthy dealers catering to even wealthier clientele with seemingly limitless disposable income to describe merchandise that is, for all intents and purposes, heavily damaged (though, to be fair, a watch’s dial having heavy patina is in no way indicative of its movement being damaged — many of these super clone watches paypal work just fine, and merely happen to look beat to shit, dial-side). “Honest” sounds better than “patina’d,” which sounds better than “discolored,” which sounds better than “damaged,” which sounds better than “utterly and irrevocably fucked, aesthetically speaking.”

However, more and more, “honest” watches with heavy patina are breaking records at auction. Paul Newman’s 6239 Rolex Daytona fake watches with Swiss movements wasn’t exactly minty — it was “honest,” i.e. it had been used, and showed commensurate wear. It’s understandable to imagine why this was valuable to people — anyone who was a fan of Paul Newman could see this wear and more easily imagine it on his actual wrist, seeing actual use. This is much harder to do with a product that’s in better condition by virtue of, say, having sat for years in its box in a safety deposit box. When there’s patina, we can project. We can be Paul Newman a little bit. Otherwise, a watch is just a watch.

Honestly, “honest” seems like an applicable and acceptable term to use to describe these types of China super clone watches. Sure — it’s clearly a euphemism, which will always be subject to scrutiny simply by virtue of its obfuscation of clarity — but we all understand what the watch world is trying to tell us.

It’s saying that just because something is beat up and shows its age, doesn’t necessarily mean that it doesn’t have any value, or that it isn’t beautiful. In fact, it’s saying quite the opposite, which bodes well for every watch ever made.

And for everybody.